How Did Michael Jackson Changed His Skin White

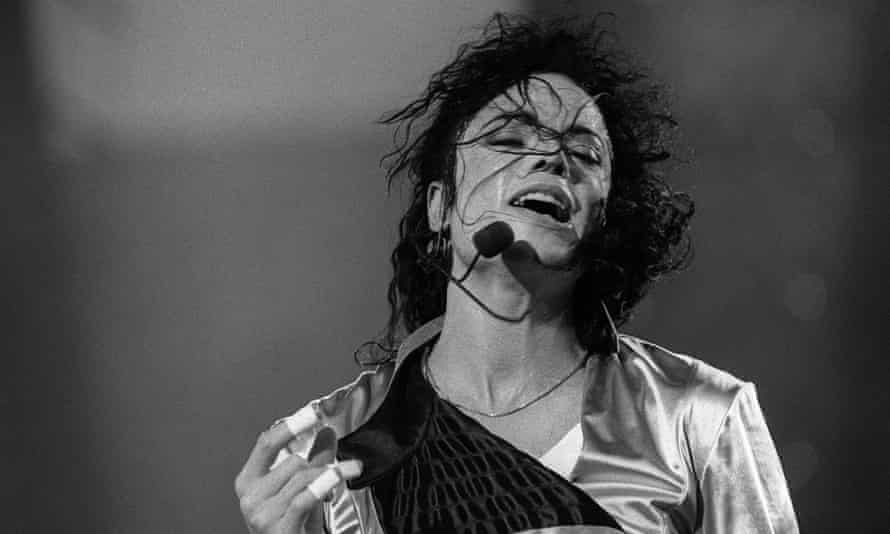

For a figure as enigmatic as Michael Jackson, one of the more fascinating paradoxes about his career is this: as he became whiter, he became blacker. Or to put it another fashion: as his skin became whiter, his piece of work became blacker.

To elaborate, we must rewind to a crucial turning point: the early 1990s. In hindsight, it represents the all-time of times and the worst of times for the creative person. In November 1991, Jackson released the first unmarried from his Dangerous album: Blackness or White, a bright, catchy pop-rock-rap fusion that soared to No 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and remained at the meridian of the charts for six weeks. Information technology was his most successful solo single since Shell Information technology.

The conversation surrounding Jackson at this point, withal, was not about his music. It was about his race. Sure, critics said, he might sing that information technology "don't matter if you're blackness or white", only then why had he turned himself white? Was he bleaching his peel? Was he ashamed of his blackness? Was he trying to appeal to every demographic, transcend every identity category in a vainglorious effort to reach greater commercial heights than Thriller?

To this day, many presume Jackson bleached his peel to become white – that it was a wilful corrective decision considering he was ashamed of his race. Notwithstanding in the mid-1980s Jackson was diagnosed with vitiligo, a pare disorder that causes loss of pigmentation in patches on the body. According to those close to him, it was an excruciatingly humiliating personal challenge, ane in which he went to cracking lengths to hide through long-sleeve shirts, hats, gloves, sunglasses and masks. When Jackson died in 2009, his autopsy definitively confirmed he had vitiligo, as did his medical history.

However, in the early 1990s, the public were sceptical to say the least. Jackson first publicly revealed he had vitiligo in a widely watched 1993 interview with Oprah Winfrey. "This is the situation," he explained. "I have a pare disorder that destroys the pigmentation of the skin. Information technology is something I cannot help, OK? Simply when people make upwardly stories that I don't want to be what I am information technology hurts me … It's a problem for me that I can't control." Jackson did acknowledge having plastic surgery merely said he was "horrified" that people ended that he didn't want to be black. "I am a black American," he alleged. "I am proud of my race. I am proud of who I am."

For Jackson, then, there was no ambivalence about his racial identity and heritage. His skin had changed but his race had non. In fact, if anything his identification as a blackness creative person had grown stronger. The offset indication of this came in the video for Black or White. Watched by an unprecedented global audience of 500 million viewers, information technology was Jackson'southward biggest platform ever; a platform, it should be noted, that he earned by breaking down racial barriers at MTV with his groundbreaking short films from Thriller.

The first few minutes of the Black or White video seemed relatively benign and consistent with the utopian calls of previous songs (Can You Feel Information technology, We Are the Earth, Man in the Mirror). Jackson, adorned in contrasting black-and-white clothes, travels across the globe, fluidly adapting his dance moves to whatsoever culture or country he finds himself in. He acts as a kind of cosmopolitan shaman, performing alongside Africans, Native Americans, Thais, Indians and Russians, attempting, it seems, to instruct the recliner-spring White American Father (played by George Wendt) about the beauties of difference and diverseness. The chief portion of the video culminates with the groundbreaking "morphing sequence," in which ebullient faces of diverse races seamlessly blend from one to another. The message seemed to be that we are all role of the homo family unit – distinct but connected – regardless of cosmetic variations.

In the historic period of Trump and the resurgence of white nationalism, even that multicultural message remains vital. Just that'southward not all Jackson had to say. Just when the director (John Landis) yells "Cut!" nosotros see a black panther lurking off the soundstage to a back alley. The coda that follows became Jackson's riskiest artistic move to this point in his career – particularly given the expectations of his "family-friendly" audience. In contrast to the upbeat, more often than not optimistic tone of the primary portion of the video, Jackson unleashes a flurry of unbridled rage, pain and aggression. He bashes a automobile in with a crowbar; he grabs and rubs himself; he grunts and screams; he throws a trash can into a storefront (echoing the controversial climax of Spike Lee's 1989 pic, Practice the Right Matter), before falling to his knees and tearing off his shirt. The video ends with Homer Simpson, another White American Begetter, taking the remote from his son, Bart, and turning off the Idiot box. That censorious move proved prescient.

The and then-called "panther trip the light fantastic toe" caused an uproar; more then, ironically, than annihilation put out that year by Nirvana or Guns N' Roses. Fox, the The states station that originally aired the video, was bombarded with complaints. In a front folio story, Entertainment Weekly described it every bit "Michael Jackson's Video Nightmare". Eventually, relenting to pressure, Fox and MTV excised the final iv minutes of the video.

However amongst the controversy (most in the media simply dismissed information technology as a "publicity stunt"), very few asked the simple question: what did it mean? Couched in betwixt the Rodney Male monarch beating and the Los Angeles riots, it seems crazy in retrospect not to interpret the short film in that context. Racial tensions in the U.s., in LA in particular, were hot. In this climate, Michael Jackson – the world'southward most famous black entertainer – made a short film in which he escapes the confines of the Hollywood sound stage, transforms into a black panther and channels the pent-upward rage and indignation of a nation and moment. Jackson himself subsequently explained that in the coda he wanted "to exercise a dance number where I [could] allow out my frustration about injustice and prejudice and racism and bigotry, and inside the dance I became upset and let go."

The Blackness or White brusk picture was no anomaly in its racial messaging. The Dangerous album, from its songs to its short films, non only highlights black talent, styles and sounds, but besides acts every bit a kind of tribute to black culture. Peradventure the most obvious instance of this is the video for Remember the Fourth dimension. Featuring some of the era'south virtually prominent black luminaries – Magic Johnson, Eddie Murphy and Iman – the video is set in ancient Egypt. In contrast to Hollywood'due south stereotypical representations of African Americans as servants, Jackson presents them here every bit royalty.

Promised a sizable production budget, Jackson enlisted John Singleton, a immature, rising black managing director coming off the success of Boyz N the Hood, for which he received an Oscar nomination. Jackson and Singleton'southward collaboration resulted in ane of the most lavish and memorable music videos of his career, highlighted by the intricate, hieroglyphic hip-hop trip the light fantastic toe sequence (choreographed by Fatima Robinson). Over again, in this video, Jackson appeared whiter than ever, just the video – directed, choreographed by and featuring black talent – was a celebration of blackness history, art, and beauty.

The song, in fact, was produced and co-written by another young black ascension star, Teddy Riley, the architect of new jack swing. Prior to Riley, Jackson had reached out to a range of other blackness artists and producers, including LA Reid, Babyface, Bryan Loren and LL Cool J, searching for someone with whom he could develop a new, mail-Quincy Jones sound. He institute what he was looking for in Riley, whose grooves contained the punch of hip-hop, the swing of jazz and the chords of the black church. Call back the Time is perhaps their best-known collaboration, with its warm organ bedrock and tight drum machine crush. It became a huge hit on black radio, and reached No 1 on Billboard's R&B/hip-hop chart.

The showtime six tracks on Dangerous are Jackson-Riley collaborations. They sounded like nothing Jackson had done before, from the glass-shattering, horn-flavoured verve of Jam to the factory-forged, industrial funk of the title runway. In place of Thriller'southward pristine crossover R&B and Bad's cinematic drama are a sound and message that are more raw, urgent and attuned to the streets. On She Drives Me Wild, the artist builds an entire song around street sounds: engines; horns; slamming doors and sirens. On several other songs Jackson integrated rap, 1 of the outset pop artists – forth with Prince – to do and so.

Dangerous went on to go Jackson's best-selling album later on Thriller, shifting 7m copies in the US and more than 32m copies worldwide. All the same at the time, many viewed it as Jackson's last drastic attempt to reclaim his throne. When Nirvana's Nevermind replaced Unsafe at the top of the charts in the second week of Jan 1992, white rock critics gleefully declared the King of Pop's reign over. It'southward easy to see the symbolism of that moment. All the same Dangerous has aged well. Returning to it now, without the hype or biases that accompanied its release in the early 90s, one gets a clearer sense of its significance. Like Nevermind, information technology surveyed the cultural scene – and the internal anguish of its creator – in compelling ways. Moreover, it could be argued that Dangerous was just as significant to the transformation of blackness music (R&B/new jack swing) as Nevermind was to white music (alternative/grunge). The contemporary music scene is certainly far more indebted to Unsafe ( ie Finesse, the recent new jack-inflected unmarried from Bruno Mars and Cardi B).

Only recently, even so, accept critics begun to reassess the significance of Dangerous. In a 2009 Guardian article, it is referred to as Jackson'south "true career high." In her book on the album for Bloomsbury's 33 ⅓ serial, Susan Fast describes Dangerous as the creative person's "coming of historic period album". The record, she writes, "offers Jackson on a threshold, finally inhabiting machismo – isn't this what so many said was missing? – and doing so through an immersion in black music that would but continue to deepen in his afterwards work."

That immersion continued as well in his visual work, which, in improver to Black or White and Remember the Time, showcased the elegant athleticism of basketball superstar Michael Jordan in the music video for Jam and the palpable sensuality of Naomi Campbell in the sepia-coloured short picture show for In the Closet. A few years later, he worked with Spike Lee on the most pointed racial salvo of his career, They Don't Care About Us, which has been resurrected as an canticle for the Black Lives Matter movement. However, critics, comedians and the public alike connected to propose Jackson was ashamed of his race. "Just in America," went a common joke, "can a poor black boy abound up to be a rich white woman."

Nonetheless Jackson demonstrated that race is about more mere pigmentation or physical features. While his skin became whiter, his work in the 1990s was never more than infused with blackness pride, talent, inspiration and culture.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/mar/17/black-and-white-how-dangerous-kicked-off-michael-jacksons-race-paradox

Posted by: maglioneaboustinger.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Michael Jackson Changed His Skin White"

Post a Comment